Across the suburbs, they’re lining up for home inspections. With COVID-19 restrictions, only a handful are allowed in at a time. The queues, for units in particular, stretch down the stairwells and spill outside. In some regional areas, particularly coastal locales, the situation has reached fever pitch.

Prices in some areas are up by more than a third in the space of a year as cashed-up buyers fleeing the cities head for the country with dreams of permanently working from home.

Regional prices rose 1.6 per cent in January, more than double that of the main capital cities.

Auction clearance rates are hurtling towards a perfect score in some cities.

Canberra recently clocked up clearances in excess of 90 per cent while Sydney has pushed way above 80 per cent; rates that indicate extremely tight conditions.

When Corelogic tallied the final numbers on Friday, the previous weekend’s national auction clearance rate hit a six-year high at 79.3 per cent.

The preliminary results from Saturday indicate an even stronger performance at more than 86 per cent.

A fortnight ago, Australian real estate prices lurched back into record territory — and there is no end in sight.

With interest rates locked in at a whisker above zero — and with Reserve Bank assurances they’ll stay put for the next four years — it’s little wonder buyers are scrambling for a piece of the action.

Add in the imminent removal of responsible lending laws and the stage is set for a sustained real estate boom.

Even accounting for the hyperbole usually employed by the industry, this note dropped into your diarist’s inbox over the weekend from a local agent summed it all up.

“In my 25 years of working in the industry, conditions have never been stronger.”

Nothing to see here

In ordinary circumstances, we’d be at the point where a rational Reserve Bank governor would be expressing concerns, perhaps even warning would-be home buyers that prices don’t always rise, and that caution is warranted in such a frenzied environment.

Behind the scenes, you’d expect contingency plans being formulated on how to deflate the real estate bubble without hurting the broader economy.

Not this time. Instead, our monetary mandarins are doing the opposite. They’re stepping aside, more than happy to let prices rip.

“There’s a lot of focus at the moment on the fact that housing prices are rising again, and the stock market has been strong,” RBA Governor Philip Lowe said recently.

“Well, the national house price index today is where it was four years ago … and the equity market, we’re back to where we were at the beginning of last year.”

He’s absolutely correct, of course.

Statistically, you could argue prices have barely moved in years.

The only problem with that line of logic is that it ignores what has taken place in the meantime.

Like, four years ago when the RBA, in a desperate bid to curb a runaway housing market, urged the banking regulator APRA to clamp down on interest-only loans, the preferred financing for investors.

It successfully muscled values lower and maintained the pressure.

Clearly, it was worried about a real estate bubble then.

Here we are again, and the most extraordinary thing is that we’ve just emerged from the deepest recession in almost a century with an uncomfortably high unemployment rate, oodles of spare capacity, inflation dragging along in the basement and wages growth at as slow a pace as it’s ever been.

How the RBA learned to love bubbles

Once upon a time, it was a central banker’s role to rain on the parade.

Or as William McChesney Martin, head of the US Federal Reserve in 1955, explained, to “order the removal of the punchbowl just as the party was really warming up.”

The idea was to look ahead, to take preventative action and keep things on an even keel.

So what’s changed?

For a start, there’s the fragile state of the global economy.

Then there are the concerns the Federal Government is about to rip away the budgetary support for the jobless and those left vulnerable from the impact of the pandemic on vital industries like tourism.

If the Government does reduce support, that will put a greater burden on the Reserve Bank to boost growth.

And so, with conventional weaponry almost exhausted and no real appetite to push interest rates into negative territory, our economic masters have latched on to a philosophy that’s been floating around for quite a while.

It’s called the Wealth Effect and it goes like this.

If housing prices inflate and the stock market keeps rising, people will feel wealthier and they’ll start to spend.

That, in turn, will boost earnings, investment, profits and lead to higher inflation and wages.

Rate cuts were supposed to do exactly that but didn’t.

In fact, all they’ve really done is boost asset prices. And now it’s hoped, soaring asset prices will do the job.

Of course, the biggest problem with soaring real estate prices and stock markets is that they drive a mighty wedge between rich and poor.

Those with assets end up sitting pretty. Those without end up being left further behind.

Stronger for longer

There’s an old saying among investors: markets can remain irrational for far longer than you can stay solvent.

So, as irrational as the recent booms have been, there’s every indication they will go on for far longer than is healthy.

Central banks, including our own Reserve Bank, have decided that instead of taking preventative action, from removing the punchbowl, they’ll let the party go on.

It is a dangerous game, and one that can backfire.

For the “Negative Wealth Effect” — the impact on spending when financial or property markets tank — can damage growth.

Ever since the financial crisis, central banks globally have been captured by their own actions.

They’ll do almost anything to ensure markets remain buoyant regardless of the longer-term consequences.

To be fair, the RBA reckons real estate prices will have to start moderating soon for two key reasons.

One is that for the past year, we’ve had no immigration which should have reduced demand for housing.

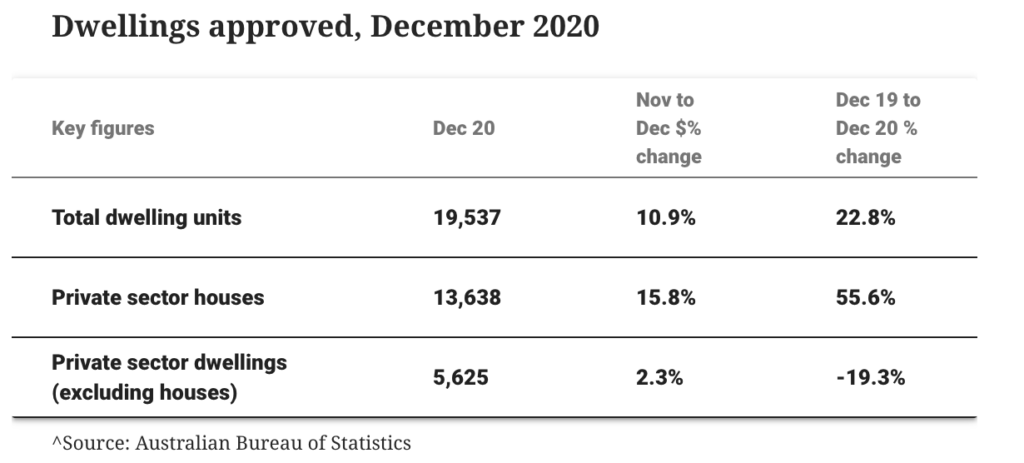

And the second is that a large number of newly constructed properties have yet to come on the market.

But if prices continue their stratospheric rise unchecked, it may be forced to look across The Ditch for inspiration.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has just raised the lending hurdles for investors after real estate surged more than 17 per cent in the past year.

So far, there’s no indication of anything like that here.